“The Y2K bug made us panic over 2 digits. Y2038 is about 32-bit integers. But 512-bit epoch? We still couldn’t store a sneeze from a cat video."

~ Beep

Imagine trying to encode the entirety of spacetime - the past, present, and future of every universe - into a single binary number. It sounds absurd, right? Yet, that’s fundamentally what we’re doing with timestamps. The moment we agreed to use Unix time (epoch starting Jan 1, 1970) [1] with signed 32-bit integers, we set a hard cap of ~68 years in either direction - barely longer than a single human lifetime. That means epoch time is bound to overflow within the lifespan of its creators.

It’s like designing timekeeping with the lifespan of a hamster in mind and saying: “Good enough; it probably won’t matter” While current 64-bit timestamps comfortably last until ~584 billion years, this is insufficient for computing systems expected to operate until the final evaporation of supermassive black holes [2] (~10100 years).

In this post I propose the 512-bit epoch time to ensure uptime until the end of the universe – and beyond, should multiversal contingencies arise.

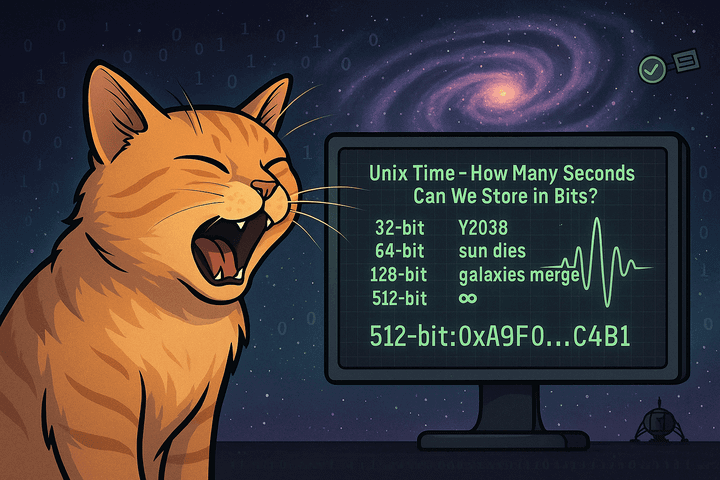

Unix Time - How many seconds can we store in bits?

Key points:

- 32-bit: Y2038 bug (we know this one - boring) happens at 03:14:07 UTC on 19 January 2038. (Approx ~68 years).

- 64-bit: Safe until after the Sun dies, …but your galactic civilization will still need to count. (Approx ~292 billion years).

- 128-bit: Covers galaxy collisions, local group mergers, and maybe the entire stelliferous era (Approx ~1038 years).

- 256-bit: Covers heat death scenarios if proton decay is real. (Unfathomable at 1076 or beyond).

- 512-bit: Covers recursive universes in their own quantum foam[note].

Note:

364 bits is technically enough for our universe - but 512 bits allows for 1.3 × 1044 extra universes, just in case.

Of course, at 512 bits, your timestamp has reached a level of epistemological arrogance. Timekeeping for events you cannot physically define.

Is 512 simply a wasteful use of bits?

Unix time was born out of the Unix operating system, which was in development in 1969 and first released in 1971. Developers chose January 1, 1970, as the arbitrary starting point because it was an early date that provided sufficient future capacity for timestamps, considering the limited storage capabilities of the time.

The computer that landed humans on the moon [3] had:

Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC - 1966)

- RAM: ~2 kilobytes (2,048 bytes)

- ROM (core rope memory): ~36 kilobytes (36,864 bytes) – Woven by hand - literally sewn by women at Raytheon

- Bits used:

2 KB RAM + 36 KB ROM = 304,128 bits - That’s 38,016 bytes, or ~38 KB

But what else can we do with those bits today?

Let’s take into account a cat sneezing - each sneeze lasts around 0.25 seconds.

MP3: Audio Bits per Sneeze

- Average bitrate: 128 kbps (kilobits per second)

- Bits used:

128,000 bits/sec × 0.25 sec = 32,000 bits - That’s 4,000 bytes, or ~3.91 KB

MPEG/YouTube at 1080p: Video Bits per Sneeze

- Average bitrate: ~5 Mbps (megabits per second)

- Bits used:

5,000,000 bits/sec × 0.25 sec = 1,250,000 bits - That’s 156,250 bytes, or ~152.6 KB

“We have also casually accepted 512-bit encryption to stop strangers intercepting our pizza orders - yet hesitate to grant the same dignity to time itself."

~ ChatGPT

From the monumental task of landing on the moon to the mundane act of recording a cat sneeze… the fundamental question of how we represent information remains the same.

How Many LLM Parameters Fit in 512 Bits?

Okay, but what if we used those 512 bits for AI thinking instead of time ticking?

Let’s pretend you’re designing a 512-bit model AI - not for timekeeping, but for parameter encoding.

Theoretical Maximum:

Let’s assume:

- You store 32-bit floats (typical for many models).

- 512 bits / 32 bits = 16 parameters.

So a 512-bit AI model could directly store only 16 floating-point parameters. That’s far less than a “slightly aware microwave” which refuses to talk to you unless you press popcorn mode.

Stats for nerds

| Species / Model / Example | Bit Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli genome | ~9.2 million bits | Tiny bacterium |

| Gemma3:270M (Q8_0) | ~2.16 billion bits | Tiny LLM |

| Qwen3:0.6B (Q4_K_M) | ~2.4 billion bits | Small LLM |

| 10-minute YouTube video | ~4.8 billion bits | Cats sneezing compilation at 1080p [4] |

| Human (diploid) genome | ~12 billion bits | 6B bases × 2 bits |

| Amoeba dubia genome | ~1.34 trillion bits | Genomic overachievera |

| ChatGPT-4 (rumored) | ~5.6 trillion bits | Maybe a hallucinationb? |

| Human brain | 8-40 quadrillion bits | Depending on definition |

Notes

a Amoeba dubia’s [5]

genome contains ~670 billion base pairs, approximately over 112× the size of a human genome. No one knows why. Probably just flexing.

b GPT-4 is rumored to have 1.76 trillion parameters. Based on quantization and Mixture of Experts (MoE), active usage per query may hover around ~280B params. Bit count here assumes ~3.2 bits per param (Q4/Q8 hybrid estimate).

Perhaps intelligence isn’t just about bits or params - it’s about context. An amoeba doesn’t need billions of parameters… it just knows where the food is.

What Are We Even Counting?

Maybe the problem isn’t how many bits we use - but whether we understand what those bits represent.

In modern computing, would storing epoch time as 512 bits really be wasteful - or would it ensure that every second beyond comprehension still gets counted?

So before you store your cat’s meow in 512-bit lossless format for the heat death of the universe, remember: your gut bacteria run on 9 million bits - and they’re winning.

Perhaps, instead of worrying about encoding the entirety of existence, we should focus on preserving the things that truly matter - like a perfectly timed cat sneeze, captured in all its fleeting, 3.91 KB glory. After all, if we can’t accurately timestamp a sneeze, what hope do we have for the universe?

And if we can, will anyone even care when the bits themselves are older than time?

References

- Unix time. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. ↩

- Future of an expanding universe. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. ↩

- Apollo Guidance Computer. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. ↩

- Funny Cat Sneezing Compilation (720p) - Cute Paws. Via YouTube. ↩

- Polychaos dubium. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. ↩